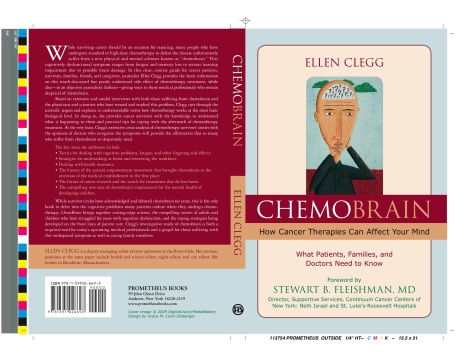

EXCERPT from “ChemoBrain” / Ellen Clegg / Prometheus / January 2009

PATRICIA IRELAND’S STORY

In a long and distinguished career as an activist for women’s rights, Patricia Ireland has fearlessly faced down powerful adversaries. As president of the National Organization for Women from 1991 to 2001, she rallied hundreds of thousands in marches for reproductive rights. She was arrested in front of the White House as she protested the military’s policies on gays and lesbians. She has spoken out for human rights around the world.

But she confronted an unexpected, high-stakes battle in 2007: she was diagnosed with acute myelomonocytic leukemia (AMML).

Ireland had been feeling tired but figured that a vacation in Barcelona with friends would recharge her. “I had been a little tired, but it was the holiday season, and frankly, like most of my friends, I have been a little tired my whole adult life,” she says in a telephone interview from her home outside Miami, where she practices law. “You know, we work too hard. We have too much going on; we are too greedy for our lives in work and family and play and everything. I kept saying to myself, well, I’m going away. I’ll catch up with my rest. I was really looking forward to it.”

When she arrived in Spain, she began to feel worse but chalked it up to a severe case of jet lag. By the end of the first week, she was crashing. She felt so tired and breathless that she could not walk from her bedroom to the kitchen to get a glass of water. She flew back home, where doctors tested her and found she had leukemia. The rapid growth of leukemic white cells had clogged her system and made it difficult to breathe or get enough oxygen to her brain, she says. Summoning her considerable intellect and inner resources, she embarked on a “high-risk, high-reward” course of treatment that involved chemotherapy and a donor stem cell transplant.

“I went over to Barcelona with friends, and I came back literally on death’s door. Of course, as the anniversary [of the trip and diagnosis] came around, I started imagining it was going to happen again. I had to talk myself into the fact that, well, if it did, I’d had a really good year. I’d bought myself some excellent time.”

CHEMOBRAIN DESCENDS

The first time she heard the term chemobrain was in the hospital when she was undergoing chemotherapy. Talking to a nurse, Ireland suddenly couldn’t find the right words. “She just laughed and said, ‘Oh, chemobrain,’” Ireland says. “And that was literally the first time I heard it. I was quite taken aback by it. I thought, what a terrible thing to hear now. Of course, no one told me about chemo curls, either, but that has a much less disastrous consequence!” Ireland adds, joking, “And in fact I have decided that as long as I have chemo curls, I can claim chemobrain.”

Ireland had a full week of chemotherapy on the first round of treatment then began consolidation therapy, where patients receive a combination of drugs over several days’ time. The goal is to achieve “molecular remission,” according to specialists. Two and a half months after the consolidation therapy, she went in for her transplant. Before she received the donor cells, she had another round of chemo to partially suppress her immune system.

Ireland recovered, chemo curls and all, and returned to work part time in the fall of 2007. But even though she thought she was well on the road to having her brain “back in gear,” problems with short-term memory and her ability to recall words lingered.

DRIVING ON CHEMO

One sobering incident occurred when she was driving to a nearby hospital for blood tests. While Ireland concedes that she is not the most attentive driver under the best of circumstances, what happened next left her baffled: She drove to the hospital and got the tests, but when she tried to go home, she drove past her house. “I have no recollection of going past my house, but the next thing I was really aware of, I was several blocks north of where I lived and wasn’t quite sure of where I was. I had to turn around and go back to find my own house. I’ve had that place since 1970, and I was only a couple of blocks north, but I simply couldn’t be sure where I was. And I realized then that my concentration and cognition were both still seriously impaired.”

She didn’t try driving again for a number of weeks. When she got behind the wheel again, she repeated a kind of mantra to herself: Concentrate, stare at the road, you’re driving. Gone were the days when she drove with one hand and rummaged in her purse for directions with the other.

‘I WAS WHOLLY DEPENDENT’

“I have difficulty accepting help under the best of circumstances, and yet I was wholly dependent on other people [for a while] to drive me around. And this was after I was supposed to be out and recovered as far as I was concerned. It made me realize that all of those warnings that they did give in the written materials were right: They said the patient and her family have to maintain a certain degree of patience because you will not be well as quickly as you think you should.”

Not one of the brochures—and Ireland read volumes of information on her treatment—mentioned chemobrain.

Ireland stresses that she is doing fine but acknowledges that her experience with chemobrain has taken an adjustment. She values her intellectual life, her ability to think and reason and live in a rapid-fire world of conversations and debate. “I always say this about beauty queens and football players and basketball players: You’d better have something else to value because your conventional beauty passes quickly, as does your athletic ability. You’ve got the rest of your life to live. I thought, OK, great, I’ve got a brain that’s going to keep going and I’m in a profession where experience is valued. And so a few gray hairs, a few extra wrinkles. . . . People think you’ve really had a lot of experience, you really must know a little bit about what you’re doing.”

It can be hard, at times, so Ireland reminds herself to hold onto her initial emotion, which was a sense of overwhelming gratitude just to be alive—“to have all this beauty around me and to have all these friends, and to say, OK, even if I never get my brain power back any more than it is now, I can still work.”

SHE ACCEPTS THE TRADEOFFS

She wishes she had been forewarned about chemobrain—she would have considered its effects and known what to expect as she evaluated the consequences of the treatment that saved her life. Yet she accepts the tradeoffs.

“I do wish somebody had told me. Of all the things that I expected, this. . . .” She pauses. “I just like to know what’s coming. It’s like any of the treatments that they gave me that were painful, and I certainly did redefine pain along the way. If I knew that it was coming, I was better off.”

She hopes that future research focuses on causes and advances in treatment. “In that sense, if there are research dollars to be spent, while I would like to have some way to figure out how to not have chemobrain or get rid of it quicker or get rid of it more thoroughly, I’d still rather have them focus on what are the causes of cancer, and [the question of ] how we prevent this?”

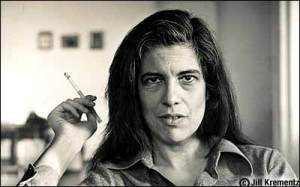

SUSAN SONTAG’S STORY

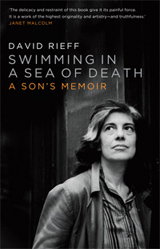

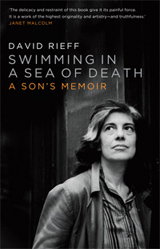

Writer Susan Sontag, the novelist and social critic who died in 2004 after her third encounter with cancer, found that she was somewhat cognitively impaired after chemotherapy. “I think my mother found, and I found being around her, that chemotherapy itself short-circuits a lot of cognitive ability,” says her son, journalist David Rieff, who in 2008 completed a memoir/investigation of her illness called Swimming in a Sea of Death. Sontag underwent chemotherapy treatment and an unsuccessful bone marrow transplant after her diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndrome, or MDS, in March 2004. She died in December. Sontag was treated for advanced breast cancer in 1975 and went on to write a probing book about her confrontation with her own body and with society’s fraught view of cancer, Illness as Metaphor. A second cancer, a uterine sarcoma, appeared in 1998 and necessitated further aggressive treatment.

“I think what my mother discovered, not just after the cancer that took her life, but even after the other two, was that the sense of being somewhat cognitively impaired after chemo is bigger than people thought or that doctors said,” Rieff says. “Obviously, doctors lowball things, once they’re committed to a procedure or a course of action. Good doctors give patients and family members some sense of what the price is for treatment. But once that is decided, a kind of tropism toward understating sets in, in my experience. This is not a scientific conclusion, obviously. [Doctors] want to get on with things—maybe they themselves don’t want to be touched by it all.”

SHE TALKED ABOUT ‘SOMETHING MISSING’

Rieff says his mother used to compare her sense of “fuzziness” to what her friends had described to her after having a small stroke. “She would talk about something missing, a slowness, a tendency to be more confused than she was before. There was a certain unsureness in all cognitive senses, a little fuzziness of expression, of understanding, a hesitancy,” he says. “I’m speaking just in terms of her experience of it, and I don’t know what the biochemical process is, nor have I ever looked into why people think this is so. But it just seems obvious that if you get chemotherapy, you may not function at the same level as you were before.”

Rieff says his mother used to compare her sense of “fuzziness” to what her friends had described to her after having a small stroke. “She would talk about something missing, a slowness, a tendency to be more confused than she was before. There was a certain unsureness in all cognitive senses, a little fuzziness of expression, of understanding, a hesitancy,” he says. “I’m speaking just in terms of her experience of it, and I don’t know what the biochemical process is, nor have I ever looked into why people think this is so. But it just seems obvious that if you get chemotherapy, you may not function at the same level as you were before.”

Rieff reflects on the intensity inherent in the relationship between doctor and patient: when Sontag used the term chemobrain, he says, her doctors took her seriously. “I do feel that doctors, whether sincerely or not, aren’t as prone to contradict their patients as they used to be.”

It’s seeping into websites and into the popular press — what the rest of us non-doctors read. Although no one should begin, end, or alter their treatment based on a newspaper article, the media echo chamber helps push patient empowerment movements forward. My colleague at the New York Times, Jane Gross, called attention to chemobrain with an important front-page article in April 2007.

It’s seeping into websites and into the popular press — what the rest of us non-doctors read. Although no one should begin, end, or alter their treatment based on a newspaper article, the media echo chamber helps push patient empowerment movements forward. My colleague at the New York Times, Jane Gross, called attention to chemobrain with an important front-page article in April 2007.

Rieff says his mother used to compare her sense of “fuzziness” to what her friends had described to her after having a small stroke. “She would talk about something missing, a slowness, a tendency to be more confused than she was before. There was a certain unsureness in all cognitive senses, a little fuzziness of expression, of understanding, a hesitancy,” he says. “I’m speaking just in terms of her experience of it, and I don’t know what the biochemical process is, nor have I ever looked into why people think this is so. But it just seems obvious that if you get chemotherapy, you may not function at the same level as you were before.”

Rieff says his mother used to compare her sense of “fuzziness” to what her friends had described to her after having a small stroke. “She would talk about something missing, a slowness, a tendency to be more confused than she was before. There was a certain unsureness in all cognitive senses, a little fuzziness of expression, of understanding, a hesitancy,” he says. “I’m speaking just in terms of her experience of it, and I don’t know what the biochemical process is, nor have I ever looked into why people think this is so. But it just seems obvious that if you get chemotherapy, you may not function at the same level as you were before.”